Stefan Zweig didn’t write history, but rather destiny. In Momentous Events in the History of Humankind, the Austrian author distilled centuries of tedium into flashes of electric tension. A simple yes or no, a gunshot, or a moment of inspiration formed dramatic peaks where the course of civilization hung in the balance of a single throw of the dice.

If those “Momentous Events” are the literature of destiny, the grand canvases are their iconography. Who dares question that painting illustrates all great happenings—indeed, that it freezes them at their point of maximum intensity? Although finding worthy canvas attire for Zweig’s energetic and radiant prose is no easy task, here at Target Prize Magazine, we’ve managed to clothe his work with unexpected elegance. From the despair of a falling empire to the conqueror’s arrogance, art was the first and most faithful chronicler of humanity’s crossroads.

“Zweig held a special fascination for the end of an era. Centuries later, painting revived that very arrogance.”

From the Twilight of Byzantium to the Minute of Waterloo

Zweig held a special fascination for the end of an era, for the agony of what seemed immutable. One of his most intense moments chronicles the Fall of Constantinople (1453), that instant when the last Rome surrenders to Sultan Mehmed II. It is the drama of an empire that ignores the warning until it is too late.

Painting revived that arrogance. Canvases such as “The Entry of Mahomet II into Constantinople” by Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant (1876) don’t focus on the massacre, but on the resounding triumph. The scene is a powerful editorial: the conqueror, serene and omnipotent, rides over the close of an era. The canvas radiates a sense of unstoppable force that Zweig distills in his narrative.

If the Fall of Constantinople was a slow agony, Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo (1815) was a flash of lightning. Zweig called it the “Universal Minute,” those hours when Europe’s fate hung by a thread. Art reveled in the epic scale of this disaster. Canvases like “Waterloo: The Charge of the Cavalry” by Denis Dighton are the visual equivalent of Zweig’s narrative climax. The painting is a vortex of smoke and fury that captures the moment when a dream of continental domination dissolves in mud and blood.

Vision and Genius: Immortality in a Gesture

Not all momentous events are acts of war. Zweig also recounted the grandeur of invention or geographic conquest.

The chapter on Vasco Núñez de Balboa and his sighting of the Pacific Ocean (1513) is a tale of solitary ambition and ecstasy. The painting that immortalizes this milestone, like the epic “I Take Possession of This Sea” by Augusto Ferrer Dalmau, shows the explorer in a gesture of theatrical grandeur: standing tall, with the flag snapping in the wind. The canvas acts as the definitive summary of Zweig’s narrative: a man who, through his vision, earns the right to historical immortality.

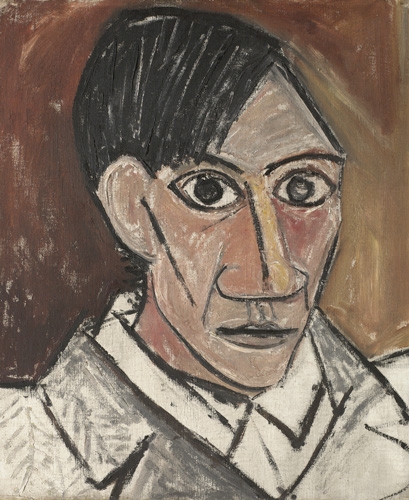

And art, too, is born from a momentous event. The story of Georg Friedrich Händel creating “The Messiah” (1741) is a tale of divine inspiration following failure. While painting cannot capture sound, it has immortalized the face of genius. Portraits of Händel, such as those by Thomas Hudson, show us a man of imposing bearing and serene determination. The canvas confronts us with the physical magnitude of the genius, who hides the emotional storm that Zweig so brilliantly set down in writing.

The Scars of the Soul: Psychological Drama

Here, the connection between Zweig and painting becomes more intimate, less focused on battle and more on human morality and the psyche.

The story of the mock execution of Fyodor Dostoevsky in 1849 is terror concentrated. Zweig narrates the intensity of knowing you are about to die, only to be pardoned at the very last second. Although there is no painting of the actual event, the psychological intensity of that “minute before the end” is etched in the “Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky” by Vasily Perov (1872). The writer’s face, melancholic and tense, seems to condense the emotional scar of that night. The painting captures the “soul” forged in that momentous instant.

Finally, the assassination of Marcus Tullius Cicero in 43 B.C. is an act of nobility. The orator refuses to flee and faces his destiny as a final act of republican dignity. Neoclassical art, in works such as “Cicero Denouncing Catiline” by Cesare Maccari (fresco, 1889), shows the orator at his moral peak. We can contrast the heroic force he radiates at his height with the tragic firmness of his final sacrifice as narrated by Zweig.

From the Twilight of Byzantium to the Minute of Waterloo

Zweig and painting share one goal: to extract the dramatic essence of events and make them enduring. Art freezes the chaos of Waterloo, magnifies a sultan’s will, or pays tribute to an explorer’s vision.

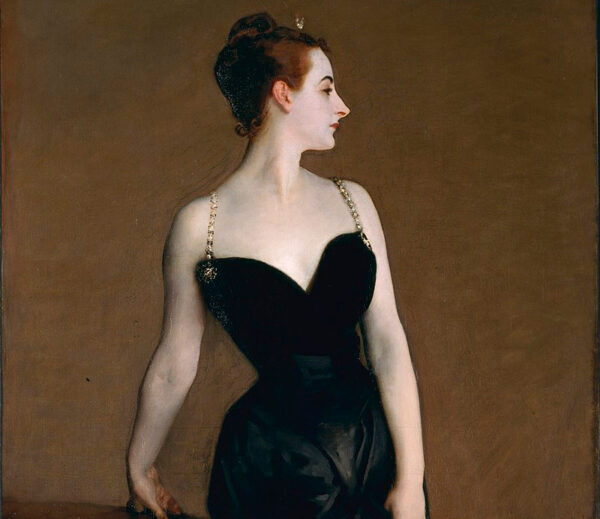

Just as in the fashion article, “The Invisible Thread of Art,” where we explained that Velázquez and Sargent dictate timeless trends, here painting acts as the definitive archivist of humanity’s turning points. It is the mirror of those Momentous Events that, like Zweig’s stars, “shining and unchangeable, gleam over the night of the ephemeral.”

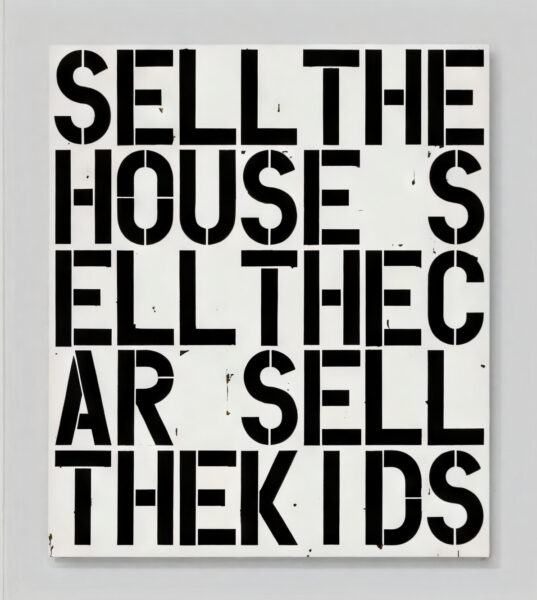

TARGET PRIZE MAGAZINE, by celebrating contemporary art, inserts itself into that same tradition: that of capturing and honoring the flashes of genius of our time. Which of today’s award-winning canvases will hold the seed of a new momentous event for future generations?