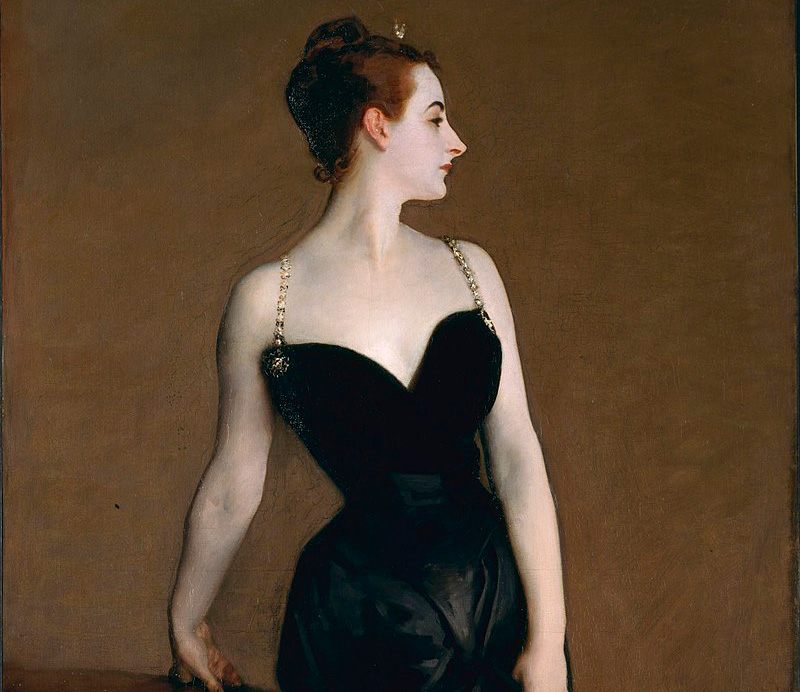

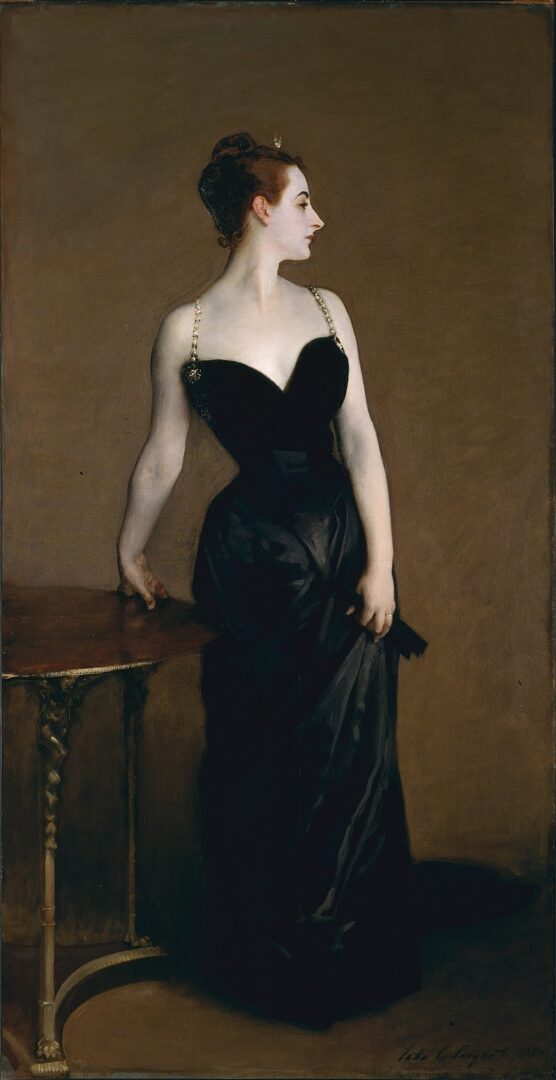

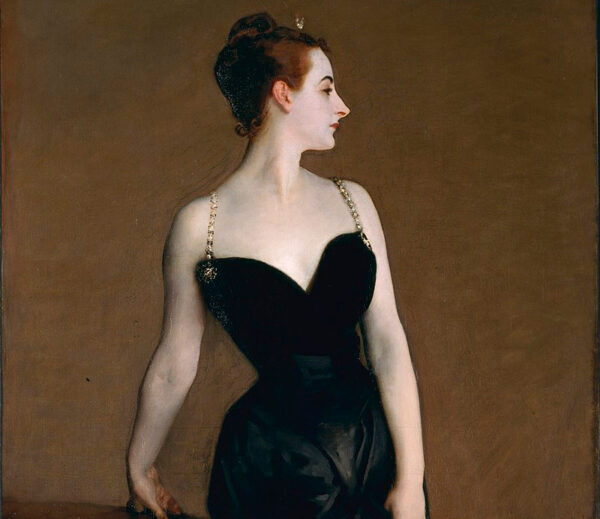

Velázquez painted queens and jesters, dressing an entire court with his brush and oil. The Baroque light of Las Meninas radiates from the attire. The masterwork of the Sevillian genius exudes fashion and etiquette, revealing power stitched by hand. Centuries later, Sargent repeated the trick with Madame X; that black neckline contrasting with pale skin, Paris in flames over a dress. Unwitting painters who became couturiers, signing their canvases like historical catalogs—motionless and timeless shop windows.

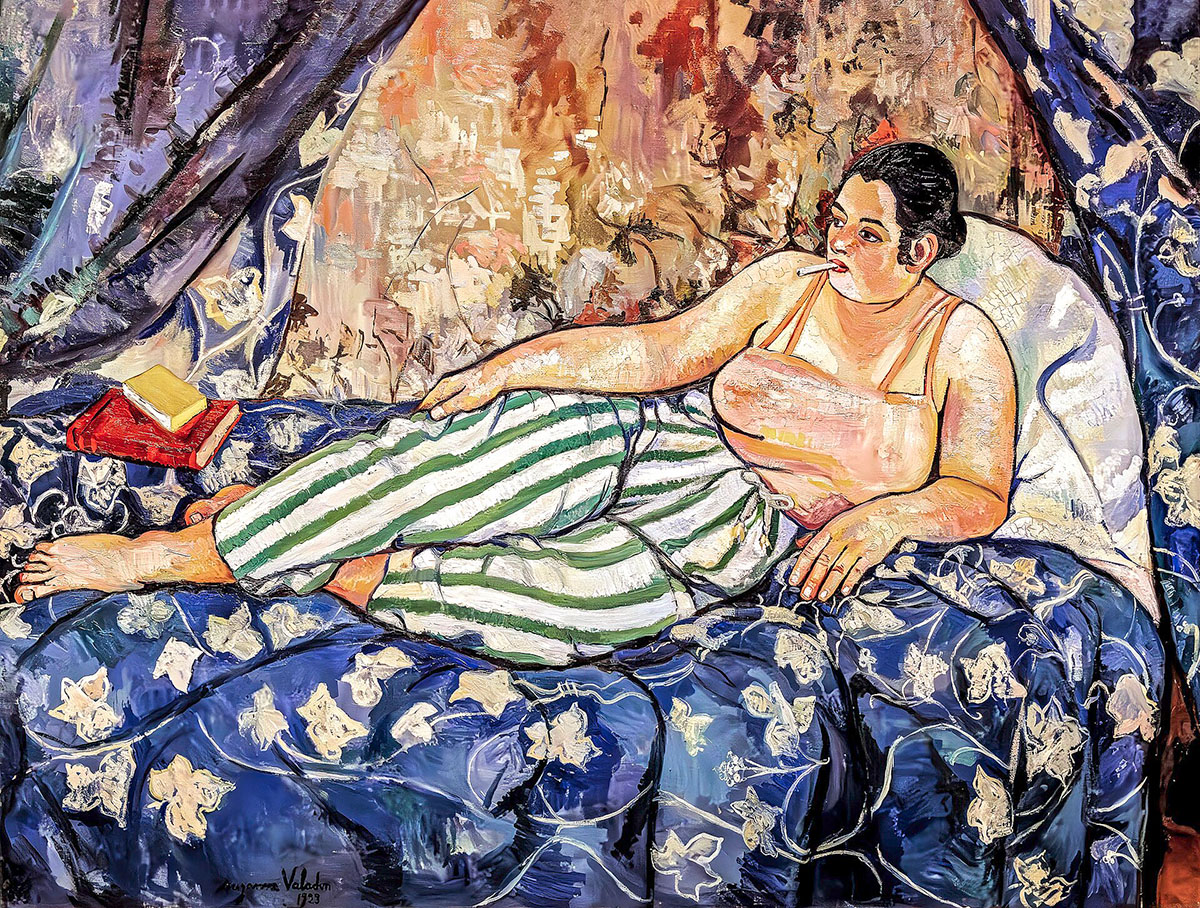

That echo still resonates in museum and gallery halls. This year, 2025, fashion continues to see itself in canvases. Du Cœur à la Main, the Dolce&Gabbana exhibition at the Grand Palais, erected a Baroque temple of fabric and glass. In London, Leigh Bowery returned in the flesh: artist, performer, a body turned into a runway. And at the Pompidou, Suzanne Valadon has been rediscovered as the painter who dressed feminine freedom in color. Three different settings for the same gesture: to fuse art and fashion, to make the canvas a scrap of velvet.

"Canvases were the first runways: you only have to look at them as if you were flipping through a fashion magazine."

Velázquez and Sargent, oil tailors

The guardainfante worn by Margarita in Las Meninas goes beyond a sense of voluminous figure; her posture is a geometry of power, an architecture of silk. Velázquez painted it as one would portray a high-fashion editorial avant la lettre. The lace, the brocades, the ruff collars… every fold is an editorial without an expiration date.

Sargent, with Madame X (1883-1884), took an even greater risk. The American artist painted his countrywoman, originally anonymous, Virginie Amélie Avegno. This New Orleans socialite posed for a portrait that scandalized Belle Époque Paris. The subject ended up living like a recluse. All it took was a fallen strap of an impeccable black dress, paired in binary harmony with her aristocratic, porcelain-like luminous skin. A scandal made of oil. The portrait was reviled, but the dress became an icon, even though the artist was forced to repaint the strap that had fallen over the right arm to put it back on the shoulder. Painting dictating trends, fashion challenging manners.

Paris Dressed by Botticelli, by Dolce&Gabbana

In January, the Grand Palais in the French capital opened its doors to an inspiring textile carnival. Twelve hundred square meters were transformed into an altar. Two hundred designs, three hundred accessories, eleven rooms as small universes. Each space, a theater. Each dress, a tribute to Italy.

On display was a coat that seemed stolen from Caravaggio himself—a spectacular garment with velvet shadows and embroidered gold lights. A dress that breathed the idyllic atmosphere of Botticelli was also admired. Its translucent chiffons mimicked the ebb and flow of waves. The Baroque, the Renaissance, opera, or Sicilian mosaic—everything was mixed in a unique, motionless parade.

Florence Müller summarized it in one sentence: “textile sculptures.” And she proved it with actions: five seamstresses from Milan embroidering live, as if thread were pigment and the needle a brush. Five tailors turning fabric into a painting.

“Fashion doesn’t just get inspired by art: it dresses it.”

The heretics: Leigh Bowery and Suzanne Valadon

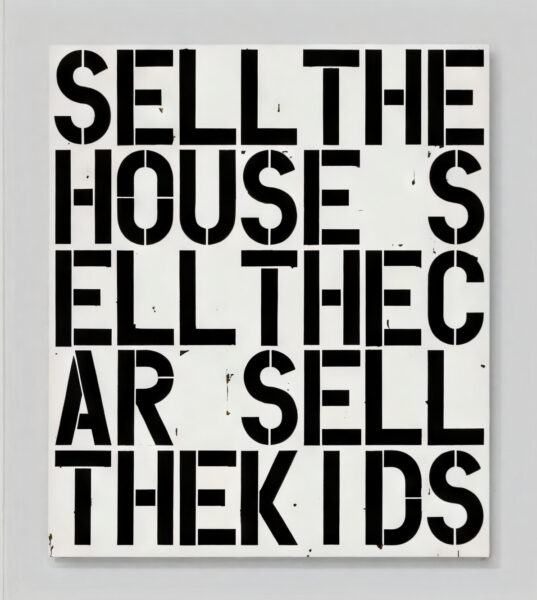

Bowery never saw fashion as an accessory. He was fashion personified. Mask, sequin, padded flesh. He sewed himself up, deforming his figure. Radical performance, an undeniable excess in the discipline of the self-portrait. His influence crept into McQueen, into Lady Gaga, into every designer who dared to see fashion as spectacle. The Tate Modern honored him with a retrospective (February–August 2025) that felt less like an exhibition and more like a nightclub—a venue that amalgamated impossible bodies, lights, and music.

Valadon, on the other hand, broke free from the canvas. From being Renoir’s muse to becoming a fierce painter. Colors like slaps, portraits without artifice, nudes that weren’t meant to please. Her Blue Room is a manifesto. There, you see a woman without a corset, without an obligatory smile, without a submissive gaze. Today, her rebellion filters into designers who aim to simultaneously reflect strength and vulnerability.

Bowery and Valadon represent the two ends of the same needle. One embroidered excess onto his own body; the other sewed freedom onto the canvas. Yet both continue to dictate codes in contemporary fashion.

“Bowery dressed excess; Valadon undressed stereotypes. Both still make fashion.”

The unseen thread that binds them

Bowery and Gaga are “sewn” together by the padded suit worn like a dress, the flesh as a canvas; excess converted into pop religion. Valadon is a precursor of the woman creator, that free palette that still pulses on runways where strength and tenderness are mixed. Meanwhile, Dolce&Gabbana connects with the classics, from Botticelli to Leonardo, from Tintoretto to Naomi Campbell. Different muses, the same desire for immortality. What can be concluded about Velázquez and Sargent, whose models were, without knowing it, the first it girls in history?

Different centuries, same impulse: the purpose of turning art into fashion and fashion into art. Canvases that breathe, dresses that speak, bodies that paint. Paris, London, Rome, the entire world as a runway.

This global dialogue also includes the Tartget Prize, which brings together artists from all over the world. Portraits, abstractions, urban landscapes… perhaps seeds of a future design. Perhaps the next guardainfante, the next black neckline, the next impossible costume is yet to be painted.

Fashion changes, art endures, but both feed each other through an unseen thread, an umbilical cord. Ultimately, every runway is a painting that walks; and every painting, a runway that still pulses.

Bibliography and Sources

Müller, Florence. Du Cœur à la Main. Dolce&Gabbana. Exhibition catalog, Grand Palais, Paris, 2025.

Pointon, Marcia. Brilliant Effects: A Cultural History of Gem Stones and Jewellery. Yale University Press, 2009. (On the relationship between fashion, jewelry, and pictorial representation).

Callen, Anthea. The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity. Yale University Press, 2000. (Context on fashion in 19th-century painting).

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. Thames & Hudson, 2020. (Chapters on Suzanne Valadon and the construction of femininity in painting).

English, Bonnie. A Cultural History of Fashion in the 20th and 21st Centuries. Bloomsbury, 2013. (Influence of artists on designers like McQueen).

Leigh Bowery: Looks. Retrospective catalog at the Tate Modern, London, 2025.

Ormond, Richard. John Singer Sargent: Portraits of the 1890s. Yale University Press, 2002.

Portús, Javier. Velázquez y la familia de Felipe IV. Museo del Prado, 2013.

Vreeland, Diana. The Eye Has to Travel. Abrams, 2011. (On the constant dialogue between fashion, art, and spectacle).

Press Articles

BBC Culture. “Who was Madame X, the society lady whose portrait scandalized Belle Époque Paris and ended up living as a recluse,” December 2023.

Le Monde. “Dolce&Gabbana fait de la haute couture une fresque italienne au Grand Palais,” January 2025.

The Guardian. “Leigh Bowery: How an outrageous performance artist reshaped fashion,” February 2025.

Le Figaro. “Suzanne Valadon au Pompidou: la femme qui peignait la liberté,” January 2025.