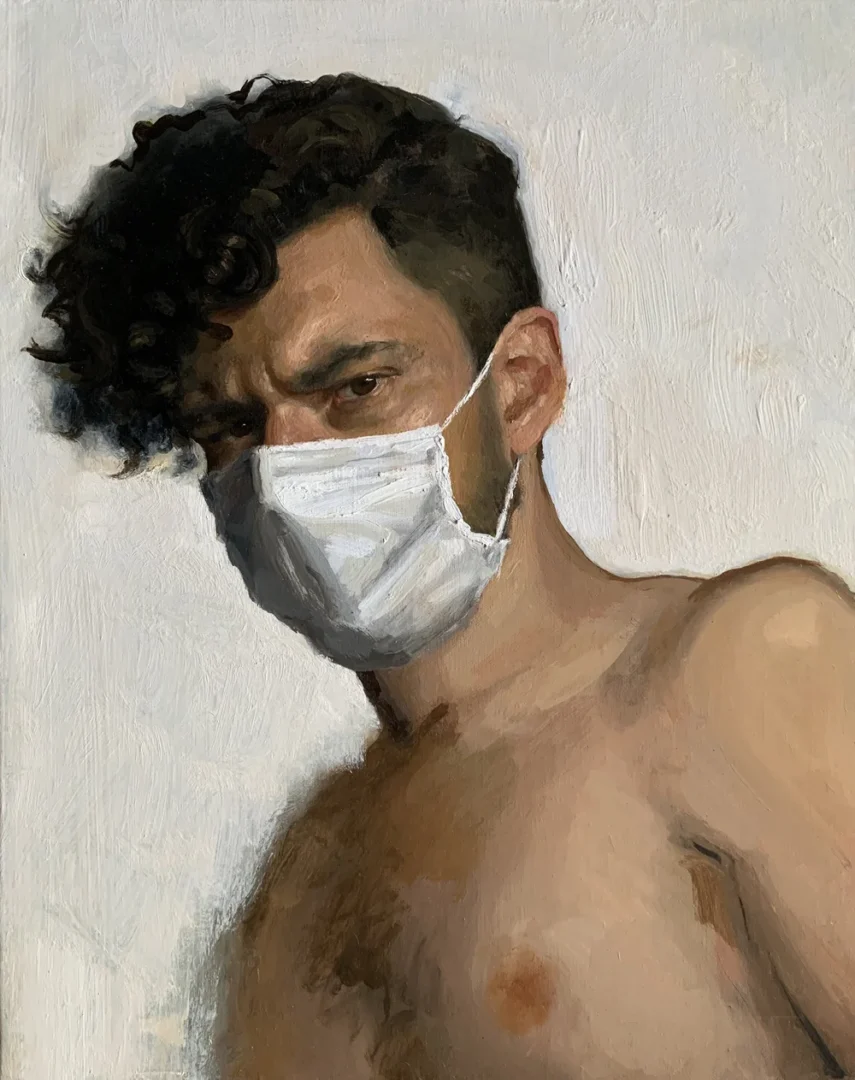

10. Brendan Fitzpatrick (2020) – The Tool as a Mirror

The Work: Self-Portrait in Sharp Relief and Social Distancing

Technique: Oil on palette knife and canvas.

Brendan Fitzpatrick does away with the physical mirror and conventional canvas. His most intimate self-portrait is captured on the humblest and most essential object in his studio: the palette knife. The artist portrays himself in what he does; his identity is inextricably linked to his craft. The tool ceases to be a means and becomes the ultimate support for his own representation, a gesture of profound material reflexivity, a powerful metaphor.

In Social Distancing, Fitzpatrick captures the spirit of an era. The mask—that new social veil—created a physical and cultural boundary, transforming us into anonymous, fragile, and fragmented entities. His work explores the paradox of connection in the midst of distance, questioning how identity is constructed when the face, our primary calling card, is partially hidden.

9. Jean-Michel Basquiat (1986) – The Embodied Urban Fury

The Work: Untitled (Self-Portrait)

Technique: Acrylic, oil, and spray on canvas.

Basquiat paints himself as an urban specter, with spray paint strokes, graphic imagery, and rawness. His self-portrait is a battlefield; primitivist iconography merges with the raw energy of graffiti and existential anguish. His gaze burns with a defiant intensity, crossed-out words and letters erupt from his head like a torrent of consciousness, and the face, often schematic like a mask, resists any attempt at simple categorization.

Basquiat, a Black artist in a predominantly white art world, uses the self-portrait to assert his identity and critique power structures. The crown that often adorns his heads is not an ornament; it is a declaration of self-coronation, elevating the marginalized artist to the status of a king or prophet.

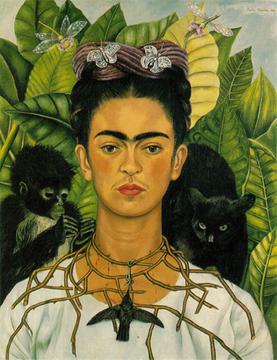

8. Frida Kahlo (1940) – Personal Mythology as Resistance

The Work: Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird

Technique: Oil on Masonite.

Frida Kahlo completely transcends mere physical representation. Her self-portrait is a personal symbolic universe where she projects her physical and emotional pain, her cultural heritage, and her indomitable strength. The thorns that pierce her neck, evoking the crown of Christ, are intertwined with a dead hummingbird—a symbol in Mexican culture of good luck in love, here ironically portrayed—while a familiar monkey and a black cat observe.

Kahlo created about 55 self-portraits, stating: “I paint myself because I am the one I know best.” Each element is a hieroglyph of her life: the cultural duality (indigenous and European roots), the suffering after her accident and miscarriages, and her resilience in the face of them.

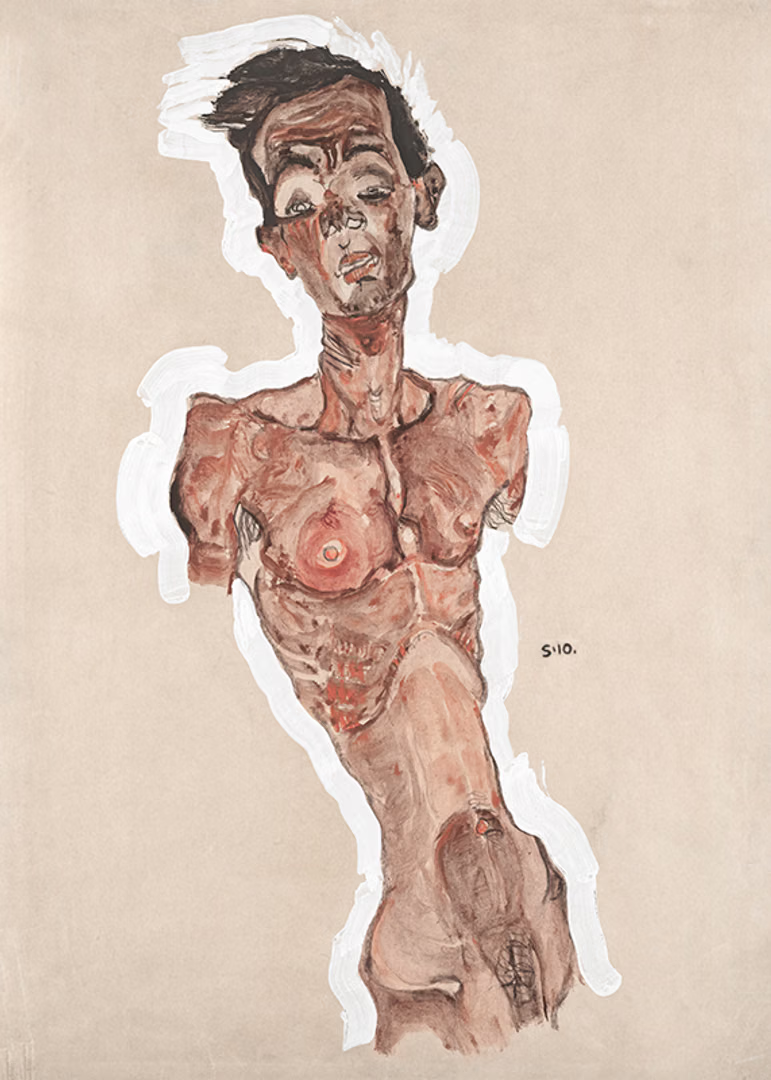

7. Egon Schiele (1912) – The Exposed Nerve

The Work: Self-Portrait with Nude Torso

Technique: Gouache, pencil, and charcoal on paper.

In Schiele’s self-portrait, there is no room for idealized beauty or harmonic composition. His body twists into unnatural angles, his skin seems stretched over a skeleton of pure nerve, and his penetrating gaze conveys a psychological intensity that is almost uncomfortable for the viewer.

Schiele belonged to the Austrian Expressionist movement, which prioritized raw emotional truth over aesthetic form. His distorted poses openly explore sexuality, vulnerability, and mortality. The cadaverous pallor of his skin contrasts with the thick, dark contours that enclose his figure, as if he is trapped within his own flesh.

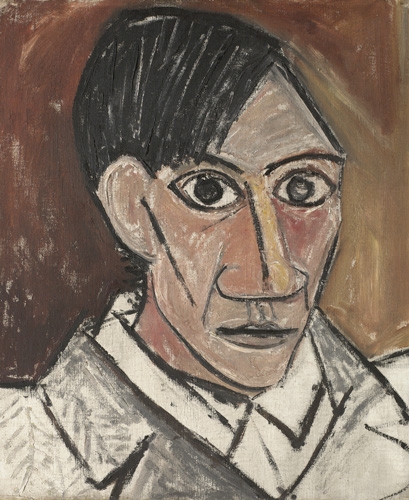

6. Pablo Picasso (1907) – The Deconstruction of the Face

The Work: Self-Portrait

Technique: Oil on canvas (56 x 46 cm).

Location: National Gallery, Prague.

At 25, Picasso dismantles himself. This self-portrait marks a crucial turning point in art history. Influenced by his recent discovery of Iberian art and African sculptures (“art nègre”), he abandons realistic and volumetric representation to adopt a geometric formal language.

His face is schematized: the eyes are large and almond-shaped, the nose a sharp triangle, and the features are folded under thick black contours reminiscent of incisions in stone or wood. This work is the direct prelude to his masterpiece, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), and to the Cubism that would revolutionize Western art.

These five artists have shown us that the self-portrait can be a palette knife, a cry, a symbol, a nerve, and geometry. They have demonstrated that the “self” is no longer a given fact, but a construction, a struggle, or a question. In our next and final installment, we will ascend to the Olympus of the genre. From the divine audacity of Dürer to the raw confession of Van Gogh, and the dignity in ruin of Rembrandt.

Bibliography/Digital Archives (Part I):

- Museu Picasso, Barcelona – Yo Picasso. Autorretratos (Exhibition catalog).

- Art in Context – “Picasso Self-Portraits – A Lifetime of Visual Self-Reflection.”

- Museo Reina Sofía – Picasso 1906. La gran transformación.

- Leopold Museum, Vienna – Egon Schiele online collection.

- Frida Kahlo Foundation – Official digital archive.

- Herrera, Hayden: Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (HarperCollins, 1983).

- Schmied, Wieland: Egon Schiele: 1890–1918 (Taschen, 2017).

- Hoban, Phoebe: Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art (Penguin, 1998).

- Varnedoe, Kirk: Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation (MoMA, 1996).

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) – Digital resources on Basquiat and Picasso.