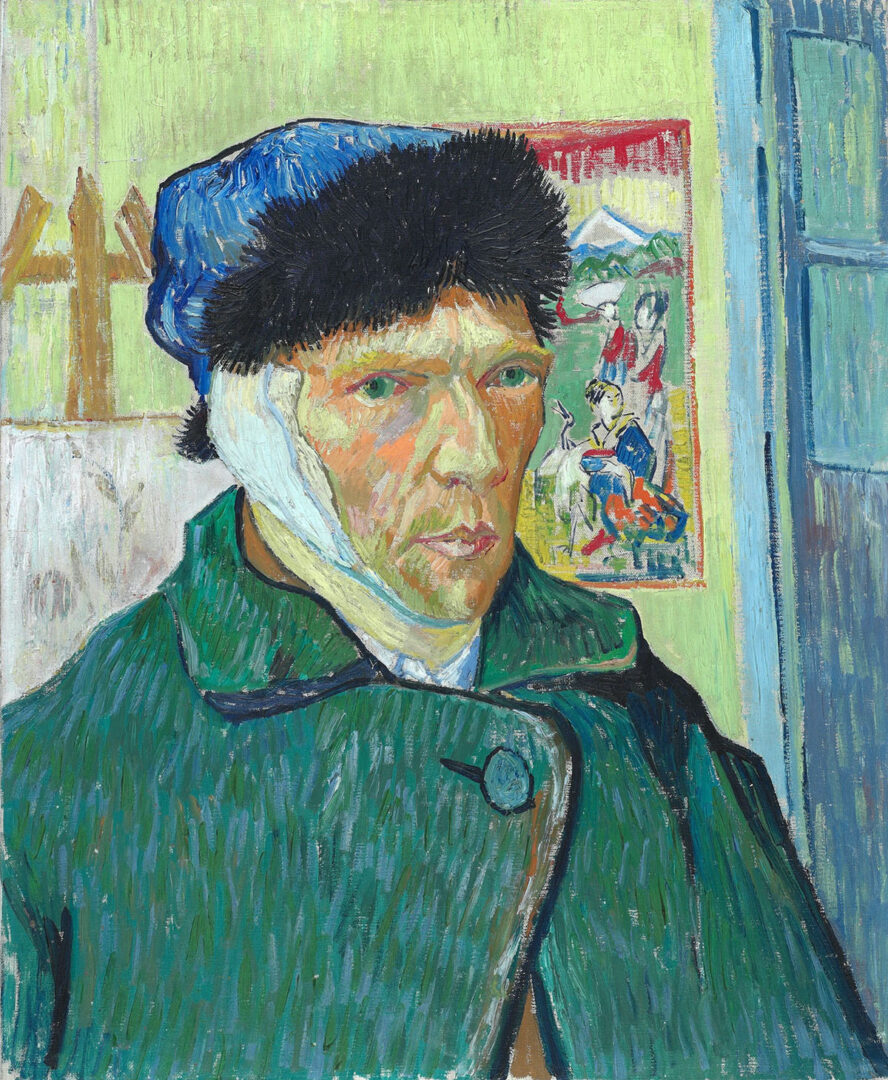

5. Vincent van Gogh (1889) – The Bleeding Confession

The Work: Self-Portrait with a Bandaged Ear

Technique: Oil on canvas

Location: Courtauld Gallery, London

The bandage covers the ear, but not the torment. Painted during his stay at the Saint-Rémy asylum following the famous incident, this self-portrait is a breathtaking testament to vulnerability and resilience. Van Gogh uses energetic, visible brushstrokes that shape his face with a palette of cool greens and blues, which contrast violently with the fiery orange of his beard and hair. His expression, however, is serene and lucid. There is no trace of madness, but rather a profound and painful clarity. The abstract background, composed of blocks of color that simulate inner vertigo, elevates his figure to an almost symbolic plane. It’s a visual statement of survival: “I’m still here, in brushstrokes.” Van Gogh uses painting not as an escape, but as the most honest medium to confront his own fractured existence.

4. Francisco de Goya (1820) – Gratitude in the Bed of Pain

The Work: Goya Attended by Doctor Arrieta

Technique: Oil on canvas

Location: Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Goya portrays himself not at a moment of glory, but in the depths of illness and vulnerability. Gaunt, pale, and clutching the sheets, he is compassionately supported by his doctor, Dr. Arrieta. The dedicatory inscription thanks the doctor for “the skill and care with which he attended him in his acute and dangerous illness.” More than a heroic self-portrait, it is an intimate history painting. The brushwork is dry and raw, faintly illuminated by candlelight that accentuates the drama. Goya does not idealize his suffering; he presents it with a direct and moving humanity. It is a portrait of the genius’s fragility, of human dependence, and of the grace of professional care at the threshold of death.

3. Rembrandt (1660) – Dignity in Ruin

The Work: Self-Portrait

Technique: Oil on canvas

Location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Rembrandt created a large number of self-portraits, including more than forty paintings, thirty-one etchings, and about seven drawings. In Target Prize, we chose the one he painted in 1660 where he shows his wrinkles as scars of time and a look that expresses his desire to keep living; a declaration of survival despite his hardships. This self-portrait speaks of bankruptcy, personal losses, and loneliness. These serious setbacks are taken on with an unbreakable integrity. Rembrandt faces the viewer without rhetoric or vanity, only with his skin and his story. Recent technical investigations reveal how he used the opposite end of the brush to incise the rebellious curls escaping from his cap, a testament to his technical mastery even in adversity. Dressed likely in his humble work clothes, Rembrandt transcends the individual to speak of the universal human condition. His gaze, bathed in shadows, does not judge, but understands.

2. Caravaggio (1610) – Condemnation as a Mirror

The Work: David with the Head of Goliath

Technique: Oil on canvas

Location: Borghese Gallery, Rome

In his last known work, Caravaggio creates the most harrowing self-portrait in art history: he paints himself as the decapitated, bleeding head of the giant Goliath. The somber, young David, more than a conqueror, seems to contemplate the fruit of his violence with sorrow and reflection. This work is a confession and an atonement. Caravaggio, a violent and fugitive man condemned to death for murder, identifies with the defeated sinner. The giant’s head, frozen and contorted by death, is a brutal reflection of his own face, marked by suffering and guilt. It is a violent, wordless prayer, a final and desperate appeal for mercy, perhaps directed at his potential patrons to obtain a pardon. Caravaggio transforms the mirror into an instrument of final judgment.

1. Albrecht Dürer (1500) – The Artist as Divinity

The Work: Self-Portrait at 28

Technique: Oil on wood panel

Location: Alte Pinakothek, Munich

At 28, Dürer paints himself with an evangelical frontality reserved exclusively for late medieval representations of Christ. His serene and direct gaze, the gaunt and delicate hand holding the collar of his fur coat, and the inscription that reaffirms his authorship, turn the painting into a programmatic manifesto. This pose is not arrogant; it is a revolutionary affirmation of the intellectual and social dignity of the artist in the Northern Renaissance. Dürer, a humanist and theorist, does not present himself as a humble craftsman; he shows himself as an alter Deus, a Creator in the highest sense of the word. The obsessive technical mastery—each hair on his head, each curl—projects a vocation for eternity. He doesn’t paint a man; he paints an idea: that of the artistic genius as a beacon of civilization.

Bibliography/Digital Archives (Part II):

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam – Digital Collection and Technical Studies

Courtauld Gallery, London – Curatorial Archives on Van Gogh

Minneapolis Institute of Arts – Goya’s Catalogue of Works

Museo del Prado – Goya: Painting and Illness

The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Rembrandt: Works and Technical Analysis

Borghese Gallery, Rome – Caravaggio: Masterpieces and Biographical Context

Alte Pinakothek, Munich – Digital Archives on Dürer

Bailey, Martin: Masterpiece Story: Self-Portrait at 28 by Albrecht Dürer, DailyArtMagazine, 2024

Hughes, Robert: Goya, Alfred A. Knopf, 2003

Langdon, Helen: Caravaggio: A Life, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999

Koerner, Joseph Leo: The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art, University of Chicago Press, 1993

Clark, Kenneth: Rembrandt, Penguin Books, 1966

Naifeh, Steven & Smith, Gregory White: Van Gogh: The Life, Random House, 2011

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza – Resources on the Self-Portrait in Art History

Dürer Foundation – Technical Studies and Historical Documentation