Velázquez, on the other hand, stood out for his ability to capture the personality and character of his models. In his portraits of the Spanish court, such as Las Meninas, he not only portrayed royalty with majestic realism but also granted them psychological and emotional depth.

Rubens, a master of movement and sensuality, employed both professional models and ordinary people in his works. His paintings, full of action and vitality, celebrated life and the human body in all its forms and expressions. Few could compare with the successful Flemish painter in terms of his relationship with his models. Part of his fame in life had to be attributed to the close collaboration of his first wife, Isabella Brant, her niece Suzanne Fourment, and the sister of the latter, Helena Fourment, who became his second wife. Everything stayed at home, even the modesty of such “thanks” for such natural and common curves.

Neoclassicism and Romanticism: Idealization and Emotion

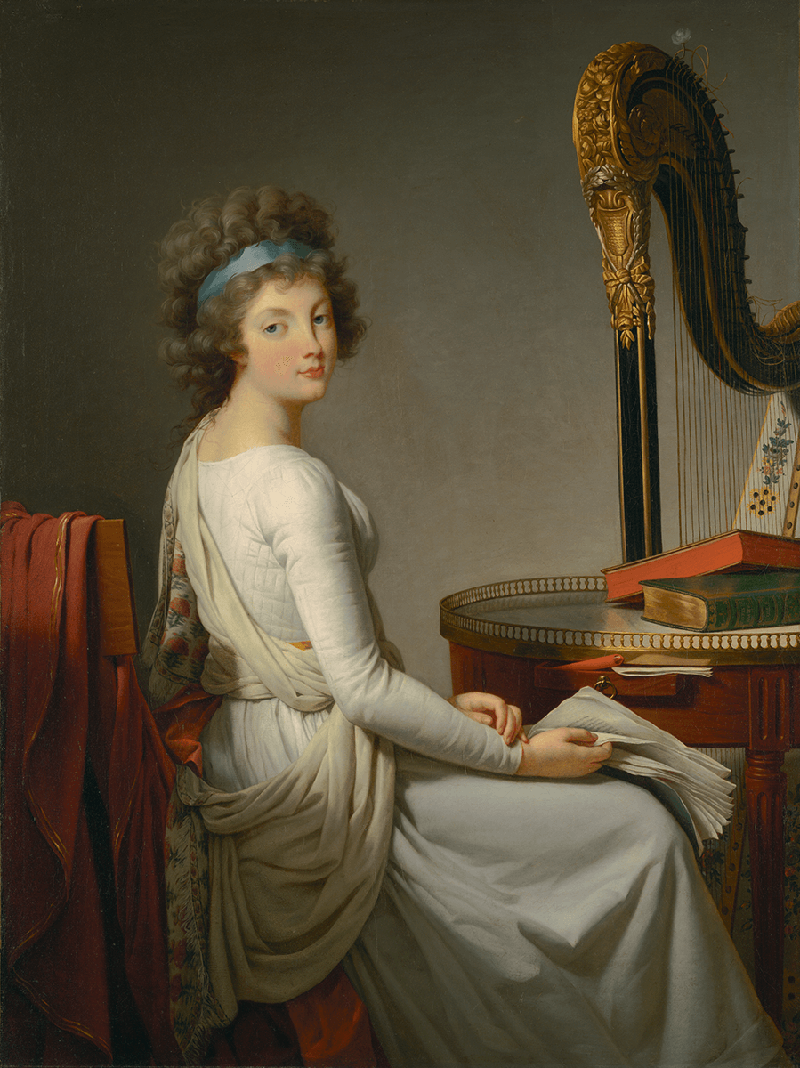

The time had come to revive the ideals of classical antiquity, to emphasize harmony, clarity, and nobility in paintings. Models, therefore, were paradigms of beauty and classical serenity. It was the moment of the vividness and perfection of a chronicler of his time like the Parisian Jacques-Louis David, adapted to the regime of his friend Robespierre and later devoted to the empire of Napoleon.

On the other hand, Romanticism valued emotion, individuality, and imagination. Models in Romantic creations were often heroic, mysterious, or melancholic figures. It was the era of exposing ideals of freedom and passion. Geniuses like Eugène Delacroix or Francisco de Goya portrayed models in emotional and tumultuous scenes, exploring themes such as love, war, and tragedy.

Some of those subjects were immortalized on canvas by the Englishman John Everett Millais. The artist from Southampton could well inspire an entire chapter himself in this series on the influence and relevance of models in the history of painting. His muse Elizabeth Siddal was an example of the relationship between artists and their models. Siddal was chosen by John Everett Millais to portray Ophelia in one of the most emblematic works of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. She floated dressed in a bathtub full of water to represent the drowning of the Shakespearean lady, and Millais painted her every day during the winter. Despite the extreme conditions, Siddal remained still for her art, and it is said that she fell seriously ill with pneumonia after one of the sessions.

Realism and Beyond: Life Truly Represented

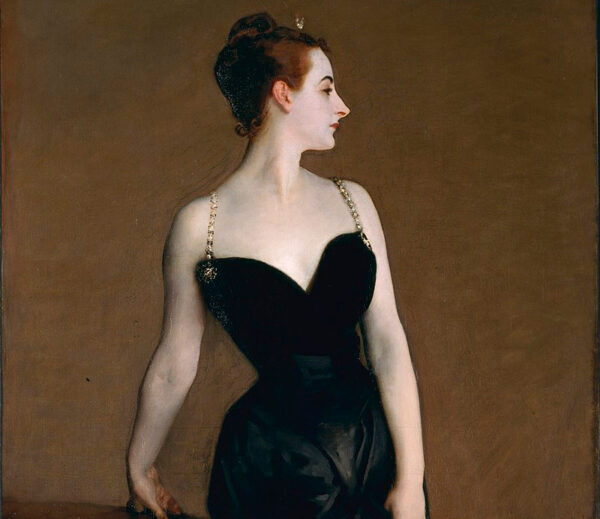

And now came the moment of faithfully representing reality to the painter’s eyes. It was the victory of Realism, the style that discarded adornments, captured the everyday, and consequently used common models. In the 19th century, artists like Gustave Courbet or Édouard Manet challenged the conventions of their time by portraying people and scenes from real life with raw honesty. A brave, sincere painting, without ideals.

Manet’s case was indeed unique and surprising. Victorine Meurent, wrongly labeled as his “muse,” revolutionized nude painting with her defiant and natural poses. But she also ended up painting herself. They became rivals, inexorably separated by creative differences. She managed to exhibit her self-portrait in 1876, while Manet was excluded. Three years later, their works shared the same room.

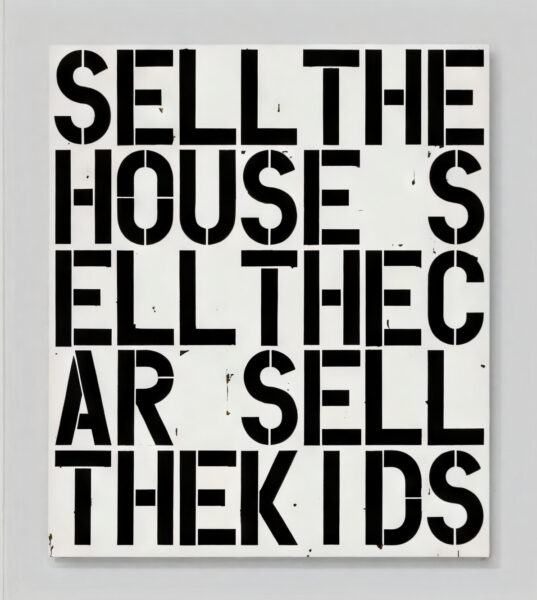

In the contemporary era, things began to get a bit more complicated, and surely something is brewing as we read these lines. Let’s wait for Part III.

Ismael Terriza Reguillos

Journalist and Communications Director of Target Painting Prize