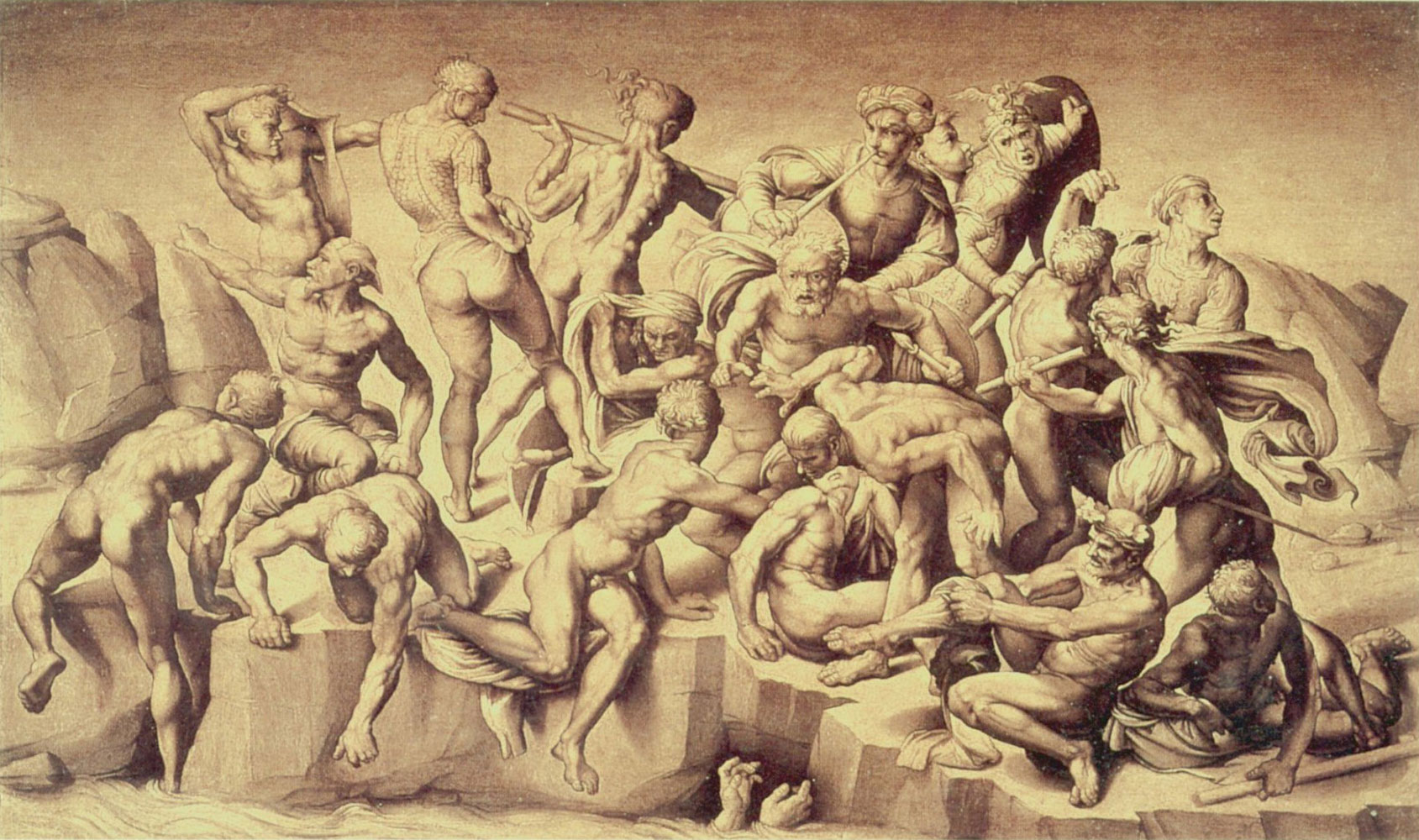

During the Renaissance, when the Italian city-states competed for cultural supremacy, public competitions prioritized the beautification of urban spaces while simultaneously showcasing the finest talents. It was within this context that two giants of art, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, faced off in one of the most famous “duels” of the medieval period.

In 1504, Florence announced a contest to decorate the walls of the Council Hall in the Palazzo Vecchio. Both masters were tasked with depicting historical battles. Though the works remained unfinished, the sketches they presented marked a turning point in art history. Leonardo contributed The Battle of Anghiari, also known as The Battle of the Standards. In this design, da Vinci displayed his extraordinary ability to capture movement and imbue his figures with vivid expressiveness. Although the original artwork was lost, copies created by artists like Rubens offer a glimpse of its profound impact.

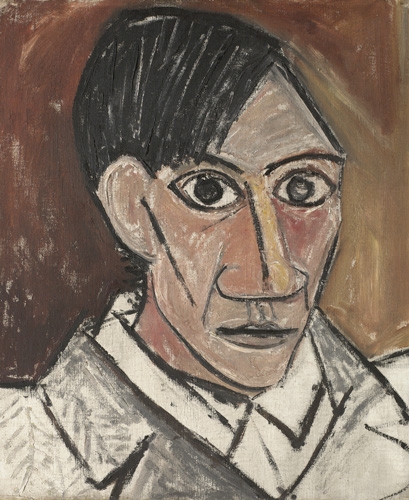

For his part, Michelangelo titled his sketch The Battle of Cascina. In this work, he delved into his profound interest in human anatomy. The dynamism of the figures would go on to set the standard for generations to come.

Although neither project was completed, both artists solidified their reputations as the geniuses of their time, and this event would go down in history as a defining moment in Renaissance art.

18th and 19th Centuries: Academic Awards and the Birth of New Schools

With the consolidation of art academies in Europe, formal competitions gained prominence. Winning the Prix de Rome, organized by the French Academy, was a prestigious recognition. This award not only guaranteed training in Italy but also the prestige needed to secure major commissions.

One of its winners was Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The artist from Occitania triumphed in 1801 with a balanced composition rich in details. He titled it The Ambassadors of Agamemnon (1801), and with this painting, he established himself as a leader of classicism. The work, measuring 1.55 meters wide and 1.1 meters high, is currently housed in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

A quarter of a century earlier, at the dawn of the French Revolution, it was another universally significant French painter who won the Prix de Rome. The Parisian Jacques-Louis David countered the creative austerity and moderation of the dying Old Regime with a sovereign display of narrative and technical mastery. The painting, created in 1774, was titled Erasistratus Discovering the Cause of Antiochus’ Illness. Also of notable dimensions, as was customary (120 cm × 155 cm), the work can be seen at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

This institution holds a collection of 450,000 pieces, including paintings, drawings, and engravings, and some of its most valuable works were acquired through the patronage of the Prix de Rome. While Jacques-Louis David once attempted suicide after several years of trying to win, other geniuses such as Eugène Delacroix, Édouard Manet, and Edgar Degas participated and did not succeed.

In the next installment, we will continue exploring more examples of how prizes, beyond consecrating their winners, have sometimes defined standards, pushing art toward new aesthetic frontiers.